In the first episode, we were introduced to the two-sided subject at Lumon. On the one hand, there is Mark S, the innie, who is screened for the first and major part of the episode. On the other, Mark Scout, the outie, to whose predicament we are introduced in the concluding scenes. S1E2 opens with a rewind on how innie Helly R came to be: how Milchick handed her flowers at end of her first day (which we glimpsed in S1E1 when Mark almost ran her over), a glimpse of her confidence gliding into the operating room on a higher floor of the same Lumon complex we saw Mark leave, a stereoscopic view of the implant procedure by which she becomes an android whose existence is "spatially dictated" by Lumon's mysterious machinations.

Lumon Industries

Lumon is a corporate pastiche, and not only of technology companies. Lumon seems to have its hands in surgical hardware (the operating room equipment), digital technology ("Macrodata Refinement"), and medicines and topical salves (as discussed at the dinner party in S1E1 - "What don't they make?"). It is a quintessentially American jack of all trades, a global power in its own right cohered by a family dynasty - the Eagans - recalling the Du Ponts or the Rockefellers.

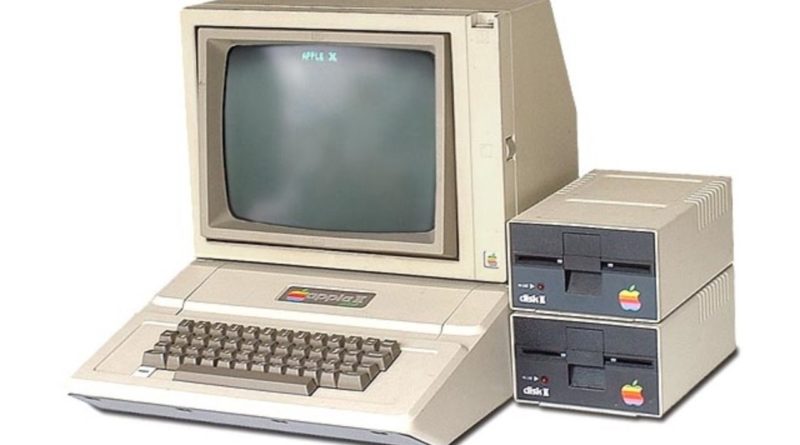

The more obvious comparison to make, however, is between Lumon and Apple, perhaps in part because the show screens on Apple TV Plus. The style of the computers on the severed floor recalls the dawn of the era of personal computing in the 1970s and 80s, an aesthetic imaginary in which Apple plays an important role.

Indeed, the aura of Lumon as a futuristic computing corporation from the late 70s is reinforced by the fact that its headquarters are shot at Bell Labs in New Jersey, a building that has now been renovated as a mixed-use office for high-tech startup companies as Bell Works. Bell Labs is the quasi-mythological source in the contemporary corporate technology culture (Silicon Valley) of the idea that a certain kind of research freedom characterized by open-ended product delivery timelines and serendipitous encounters in open office plans can cultivate ground-breaking technology. (Mark Zuckerberg recommended a book on Bell Labs as one of his 'important books' of 2015.) The irony of this setting, of course, both in Severance and in the technology companies it parodies with which we are familiar in the American landscape in 2025, is that the workplace has never been more saturated with surveillance and micro-management. The overhead shot of Helly R that opened the series is indicative here again, as is the complementary overhead of MDR's desks we get in this episode: there is always something watching from above, it seems, even if what it captures of the actual activity is a flattened and at times misrepresentative image.

There are also evocations of Microsoft and IBM in Lumon, such as the Clippy-like guide on the manual handed to Helly in the episode, or the apparent requirement of suits on the severed floor echoing IBM's infamous strict dress code. Lumon is a melange of imaginary pasts, presents, and futures in American innovation. It is futuristic in the framing of its bio-technological project of perceptual management– and in the "data smuggling" detectors that are installed in the elevators to the severed floor, about which more soon– but retrofitted in its aesthetic, in its management style, and in its outdated repertoire of daily devices. Recall, for example, Milchick's handheld camcorder, and the tube-activated (vacuum-tube?) camera he uses to snap the official photo of the new group of refiners.

The overhead of Lumon Industries itself depicts a sketchy graph of a brain, one can't help but think. Its upper floors all operate above board with normally conscious workers, whereas underground there is something sensitive enough happening so as to require extra precautions. In S1E1's analysis, we introduced the idea that Lumon's interest in severing workers has to do with the mechanics of capital, in that surplus value can only ever be produced (in Marx's account) through the structural theft of time from its laborers.1 Lumon's spatial layout suggests that there might also be a psychoanalytic metaphor at stake in severance as an operation, where the happenings that occur in the business brain's basement are essential to what it really is, why it does what it does.

Though Freud's theory has been popularized as a topographical notion, wherein the unconscious is the submerged part of the mind's iceberg of which we only see the tip, there is good reason to believe that this spatial description misrepresents how the unconscious should be properly understood. Lacan thus preferred topological descriptors to suggest that, if the unconscious is a 'place' or 'site', it contradicts any over-simplistic understanding of spaces that are distinctly separable. The relationship between the conscious and the unconscious in a psychoanalytic theory of the subject, I would suggest, is better understood through the figure of a coin with two inseparable sides. The meaning of any one side ('heads') derives from the meaning of its opposite ('tails'); and it is thus insensible to imagine separating one part from the other without repressing something fundamental about the structure of the subject as a whole.

Lumon, though, seems to want desperately to keep innies from being in contact with their outies. Indeed, the very project of severance seems to have something fundamental to do with managing repression effectively, with renovating the worker into a perfectly divided self that cannot complain about the conditions of her labor through the fact of not knowing anything about them. (When Mark is given a dinner coupon on account of his head injury in S1E1, the real cause of the scar– Helly R's riotous attempt to escape the orientation room– is not revealed to outie Mark.) The subject in Severance is split and maintained as such. The 'unconscious' of one's home life should not affect one's 'conscious' ability to perform at work.

The vice-versa is also true. Outies cannot suffer the 'unconscious' of their innies, either. Mark Scout's decision to sever himself seems to be an attempt to repress the devastating effect of his experience of his wife's death for some part of the day, given that he admits he was unable to continue his job as a history teacher due to alcoholism. At Lumon, however, Mark's alcoholism is brutally functional; as his innie must suffer what (lack of) energy he is given by outie Mark's actions the night before ("I find it helps to focus on the effects of sleep since we don’t actually get to experience it").

The intellectual impoverishment of Lumon's severed workers is further exposed in this episode as Dylan tries to convey to Helly the substance of what there is to live for as a severed innie: his "embarrassment of wealth" that consists of finger traps, a caricature portrait, and the hope that there might be a "waffle party" on the horizon. The sad satisfactions that severed workers aspire to reinvigorate the sense of the phrase "wage slavery", an important formulation that in fact has solid footing in Marx's analysis of capital. For Marx, it is worth comparing the wage worker's predicament to the slave's; for both must labor not for themselves, for their own ends and aspirations, but for an external master that appropriates their efforts. The important distinction is that, while in real slavery the slave's enthrallment to the master is explicit and explicitly enforced by means of force, in wage slavery the figure of the master is more diffuse, and hierarchical distinctions are 'justified' in the discursive suggestion of their being fairly and freely established. The proletariat (wage laborer) is free to choose her own master on the market, selling her labor power to whomever she chooses. But she is not free to refuse to sell her labor as labor-power; as this 'wage slavery' is the generalized means of her reproduction and ability to go on living. So the proletariat is enslaved to a structure, not a person, and that structure is characterized by the reduction of labor in its multifarious forms to labor-power, a measurement of labor in time that thus becomes exchangeable on the market. In capitalism, in other words, freedom is structurally reduced to the freedom to choose to whom one sell's one labor-power: which is not the same thing as freedom tout court. Thus is the wage laborer unfree in a way that is comparable, though not equivalent, to the slave.

Death at Lumon

The death culture at Lumon should also be doubly refracted through Marx's analysis of how capital reduces its workers to shadows of themselves on the one hand, and a psychoanalytic understanding of the subject on the other. When Mark gets emotional about Petey's disappearance during the game of office introductions (which tellingly involves passing around a brignt red ball), Milchick reprimands him with the following explanation:

I think this is a good time to remind ourselves that things like deaths happen outside of here. Not here. A life at Lumon is protected from such things. And I think a great potential response to that from all of you is gratitude.

Severed workers are insulated from death because the very structure of their subjectivity distances the meaning of its concept. Innies symbolically 'die' when their outies do not come back to work, but this event does not necessarily coincide with their physical death, which as Milchick suggests should only be imagined to take place in the world of their outies. There is a contradiction here, though, as a physical accident at work would propagate through to an innie's outie. So Milchick's repression of the notion of death must be recognized as just that: a repression of a certain moment in or dimension of logic (a moment that is too dangerous or frightening to imagine saying out loud), and not as an explication of logic's necessary consequences.

Milchick's philosophizing also points to something more sinister in the structure of the severed subject. The severed worker is protected from death, perhaps, because there is a sense in which he is already undead. Doomed to exist in the artificial enclosure of Lumon's basement and placated only by the pathetic enjoyments of finger traps, company coffee, ideological art, and the odd waffle party, what is there, really, to live for at Lumon? The motto briefly shown on the implant hardware in Helly's operating room scene at the episode's opening has morbid resonance here: "Don't live to work. Work to live."

There is a stronger psychoanalytic sense in which we might make sense of Milchick's discourse on death that is worth mentioning here, too. Lacan articulates a distinction between two kinds of death in his theory of the subject, a first death that is biological and a second death that is symbolic. I will explicate this theory later in S1, when Milchick's foreshadowing of death's importance in the show bubbles clearly to the surface in a later episode.

Capturing and controlling the symbolic

Let's talk about the "symbol detectors" in the elevators, which are introduced in this episode. These are the real basis of how Lumon separates innies from outies, as they supposedly ensure that no notes, no language, is passed between the two kinds of self. In S1E1, we saw outie Mark put the tissue he had been crying into in his car in his pocket; and we then saw innie Mark confidently strolling out of the elevator on the severed floor, quizzically discovering the tissue in his pocket, and tossing it into a bin on his walk down the hall to MDR. So the suggestion has already been planted in our (the viewers') mind that it is possible to traffic objects across the boundary. The other clear evidence of this is offered here in S1E2, where Irving similarly, quizzically, observes the black sooty substance underneath his fingernails during the distraction of the melon party.

Yet Helly's note to herself triggers the alarms, resulting in the elevator doors refusing to close and a screen washed out with red alert. So they do seem to have some power to detect 'symbols'. But what marks the boundary between a symbol and a non-symbol for this technology? It is not only explicit language in the form of written or spoken words that make meaning for us as human animals. We are affected by a frightening range of other things; colors, tactile memories, qualities of our past selves that seep into our present (such as too much alcohol drunk the night before). So it is hard to imagine, knowing the complexities of our selves as we all do, that Lumon could really effectively police the boundary between innies and outies, even with its 'back to the future' technological prowess.

Indeed, the audio recording that innie/outie Petey shows outie Mark in his hideout at the greenhouse reveals the insecurity of symbol detection at Lumon. In order to get a recording of what he was subjected to in the Break Room, he must have been able to get that retro handheld device back up into the 'real' world. So either the elevators weren't able to pick it up, or there is some other way for innies to move between the supposedly demarcated spaces. Either way, the symbol policing at the innie/outie border seems to have some shortcomings.

A brief note on Petey's dishevelled greenhouse to conclude, as this episode is where we are first introduced to much of the important topography in the series: the break room, wellness, MDR, optics and design, Mark's basement, the company restaurant (where Mark has his insufferably awkward date), the elevator, the MDR kitchen, the operating room, the Lumon foyer. Petey's greenhouse, like many of Severance's spaces, is a graph that both embodies and reflects a psycho-social moment of the show. Green like Macrodata Refinement, but much less put-together, the greenhouse reveals the underside of Lumon's apparent glaem, the unconscious damage that its project of perfection wreaks on its workers psychologically and physically. Petey shows us that the worker, like so many words and things in the show, is not simply what it seems, but consists also of an excess signification that inevitably creeps into its conspicuous comportment. Mark is a depressed drunkard on the outside, and Irving (it seems) has his fingers in some hellish kind of black pie, a color that takes over his desk as he dozes off when he lets the distinction between his waking and unconscious self slip, we might say, when the reality of sleep threatens the security of being awake. There is, as the imagery in the poster of the 'Whole Mind Collective' that motivates Mark to bunk off and follow up on Petey's enigmatic red letter suggests, a real revolution of sorts brewing beneath the surface of a fantasy of symbolic control.

Boštjan Nedoh has evocatively called this operation "theft without a thief".↩︎