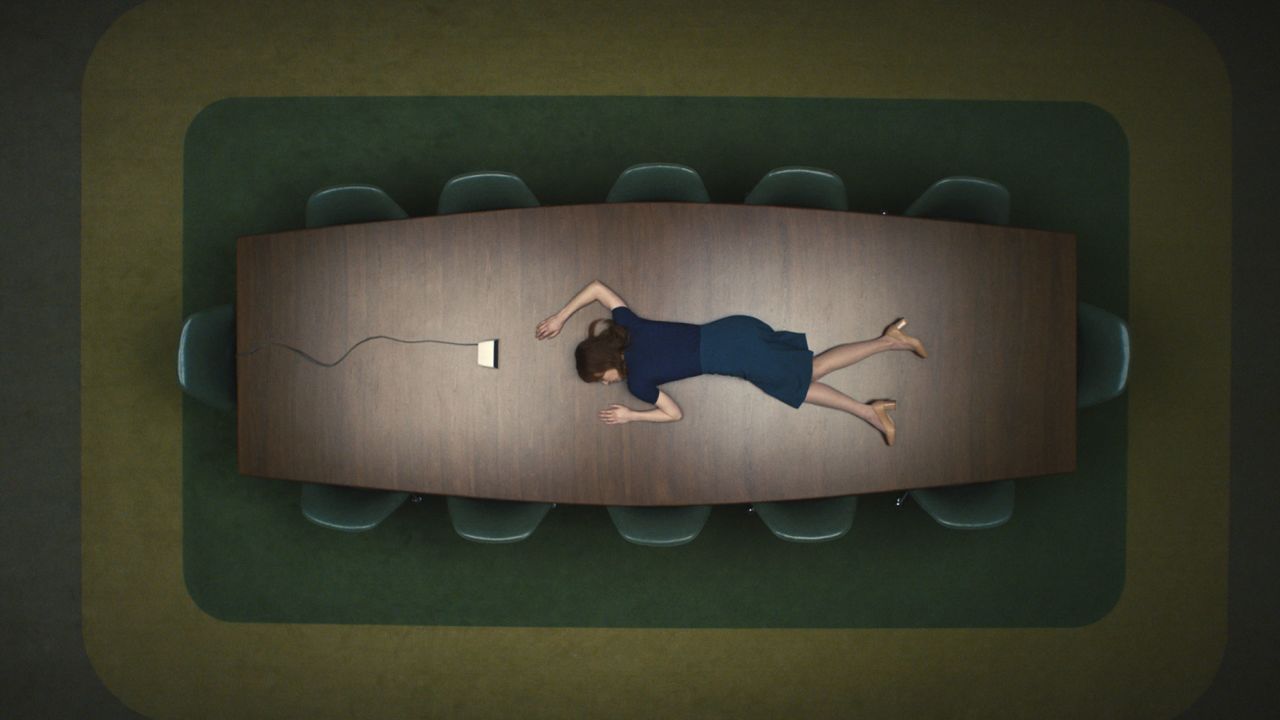

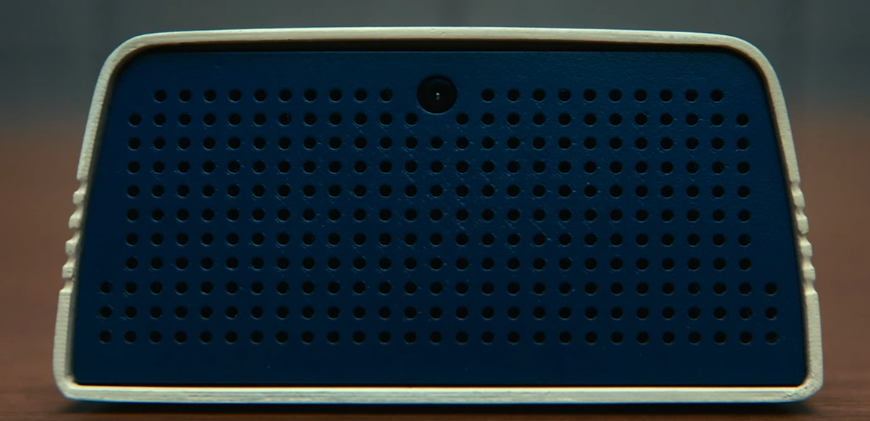

The first thing to notice is the colour palette. She is dressed in blue, but her hair is chestnut red. It spills out for the frame of her figure into the table around it, blockaded at its border by chairs and a carpet clad in green, yellow, then green again; then gray. The establishing shot is a bird's eye view of an unknown woman who is soon revealed to have been put in the board room by someone else's design, who learns about her predicament only by a man's voice that emanates from the little device that rests on the table along with the woman, arranged so that it aims directly at her head.

This opening image is a graph of the subject's predicament on the severed floor at Lumon. Blue is the company colour. Employees are almost invariably dressed in shades of it– navy, midnight, Prussian, Oxford, cobalt– and more reliably so as we work our way up the hierarchy. Red is unruly passion, the tone of tempers that itch to tear off the straitjacket directives, to disregulate the business-as-usual in which there is no obvious place for illicit activities. Green is the accent of Macro Data Refinement, the division of Lumon in which the show's protagonist are employed. The device directs a man's voice at a woman's body in an attempt to keep her tempers in check, to ensure her firecraft does not smoke out the staid edifice of personality management, to order her "perceptual chronologies" accordingly. (Later in the episode, we learn that she almost manages to "break in" on the control room during that opening sequence: the solidity of its enclosure is threatened from the very first.)

It is instructive to attempt to articulate the dynamics that this graph indexes before we start talking about other scenes in the show. Graphs are not at one with what they represent, for in the decision to render 'data' in the very act of a representation, we both lose and gain distinction of the dynamics in question. The voice that opens Helly R up to the world of Lumon's severed floor begins: "Who are you?" This question is a mistake. We retroactively learn, in a later scene, that Mark S was in fact supposed to begin with a less interrogative, more perfunctory: "Hi there, you on the table. I wonder if you'd mind taking a brief survey." As Irving puts it: "You [Mark S] skipped the preamble". Helly R is thrust, by this accident, immediately into questioning not only herself, but also the self-assurance of the voice that interrogates her. Does this voice in my head [she could be thinking] really know what it is doing? Or is it just a role of similarly confused actors struggling to stick to a badly written script?

This episode-length recap of the first episode names this graph 'the Helly incident', a poorly executed orientation of Helly's newfound subjectivity that can be blamed at one level on Mark S (for starting with the wrong part of the manual), at another on Mr. Milchick (for misguiding Mark while he was distracted setting up the visual feed), on Ms. Cobel for giving Mark Petey K's old manual without redacting his obscurely scribbled notes and paper bookmarks, or even on Irving for neglecting to intervene and clarify how Mark should begin being the more senior refiner in the situation ("Irving will be there to shadow. Just stick to the flowchart and escalate properly depending on dialectics."). Wherever to place blame, there is doubtless a misconfiguration that takes place. Helly's instinctual reaction seems to be to try to kill the voice pointed at her head, rather than to befriend it as Mark states he did (where Petey was Mark). (Helly will eventually have sex with the source of the voice, rather than murdering or fraternizing with it.) In this episode, however, Mark (the voice's source) is physically assaulted by Helly, dented in his temple by the same vocalization device that mediated their first communication.

So this is the Macro Data refiner's situation. On the one hand, she is affronted with a voice that compels her to abide by the rules and permits her to enjoy some small reliefs (egress from a locked room) if she concedes to it. On the other, she is always teeming and thus flirting with red, considering escape routes that involve drawing blood, setting off alarms, or removing clothes.

This unruly red is what Macro Data Refinement's greening procedures are supposed to contain to produce a completely controlled and scripted blot of blue. Perhaps this is why the glipse of the vacant desks planned for the severed floor's expansion are draped in purple, for that shade of subjectivity would better incorporate the contrasting contours into a unified and taskable tone. The red that threatens Lumon's corporate, calm, and collected blue (the Lumon logo is a water droplet that suspiciously resembles a camera) is splattered across scenes in the episode. It is, for example, the envelope that Petey slips Mark at the company-owned restaurant Pip's with the suggestion that he should read it if he wants to know "what's going on down there". It is the sweater Mark wears to his sister's dinnerless dinner party, punctuated by red place mats ("what a lot of people overlook, I think, is that life is not food"), where the ontological substance of his innie is called into question, and where we learn about the passions he has lost– the history of World War II, educating, whiskey– the last of which seems to have given way to an indiscriminate consumption of beer, wine, anything that will drown out the clarity of sober consciousness. It is the general hue of his sister's house, which consisently wants him to question that placid blue of his company-subsidized housing at Baird Creek Manor.

(This dinner tells us something more about the subject in question in Severance. Just as Helly's outie had alerted us to the basic principle in the video her innie was shown in curiously lo-fi resolution to conclude her innie's orientation– "perceptual chronologies… surgically split"– Mark's predicament is comparably explained to him by another more or less ignorant (we can't help but imagine) third party: "One's memories are bifurcated, so when you're at work, you have no recollection of what it is you do there." As pretentious as they are, the dinner's guests do seem to be attuned to an important dimension of the meaning of life, which is that it can't only be about satiating biological needs such as food. What each individual 'needs' is a disharmonious melange of needs and demands, openings of desire that emerge not only through a graph of bare necessities– food, water, shelter– but also through capricious carapaces that emerge from more ambiguous pinings in the social sphere– company, care, love). The real question of Lumon's smooth functioning is whether it will be able to effectively plug up these pinings, the incidental moments at work where one wonders what one is really doing with one's life, whether the company can really manage its employees' unsanctioned thoughts and the way in which those illicit ideas seep into the daily practice of their workerhood. More on the plasticity of our needs and drives to satisfy them in later posts.)

Ms. Cobel, in contrast to Helly's and Mark's doubtful and doubting red, is a stormy and icy blue. (We must wait until season two to uncover the historical and psychological depth of this colour for Harmony Cobel.) She is the figure with a body that seems to be the most in charge, of those we meet in this episode. Though Ms. Cobel is not a master in herself, it seems, for she too is subjected to a disembodied voice-via-device, "the board", albeit which only appears evidently as an ear so far ("The board won't be contributing to this meeting vocally"). Cobel is responsible for keeping the severed floor's uncertainty in check, the 'head' that sits atop the variegated limbs of its disobedient body.

When Cobel reprimands Mark for his derailing of Helly's orientation, she recalls an obscure and theological aspect of her parentage:

You know, my mother was an atheist. She used to say that there was good news and bad news about hell. The good news is, hell is just the product of a morbid human imagination. The bad news is, whatever humans can imagine, they can usually create.

At the close of the episode, just before Mark's senile neighbor Mrs. Selvig (who we have only heard about through Mark's voice thus far, when he is on the phone with er) visually reveals herself to be the same woman as Ms. Cobel, she gives a slightly different account of her heritage:

You know, my mother was a Catholic. She used to say it takes the saints eight hours to bless a sleeping child. I hope you aren’t rushing the saints.

It's unclear at this point whether Cobel is a severed worker like Mark, or whether there is some other reason for her (strange, almost senseless) duplicity. Why lie about the religious leanings of one's mother? Or maybe 'mother' is actually a name for something else, a kind of interim authority that gives synthetic weight to some hearsay, rumor, or idle phrase. (The other cameo of an ambiguously defined mother in this episode is in question five of Helly's orientation survey: "To the best of your memory, what is or was the color of your mother's eyes?") Perhaps it is that, severed or not, atheist or Catholic, Cobel's subjectivity is structured by a comparable split in her 'perceptual chronologies', whereby some memories (of her mother) get more airtime in her conscious experience of herself than others.

Severance flirts with this idea extensively, that the innie/outie dyad is analagous to the unconscious/conscious experience that we, as subjects, have of ourselves. Mark's sister Devon hints at the psycho-logical reading of the severed condition in her diagnosis of Mark's morose (outie) predicament as a state of failed therapy in response to mourning for his late wife: "I just feel like forgetting about her for eight hours a day isn’t the same thing as healing." As with not-mothers and the plasticity of the drive, we will address the psychoanalytic implications here in later posts; but to finish I want to bring our attention to the imaging of time at work in just this first episode.

The fascinating details of failed synchronisation between all the watchfaces we see are enumerated in this Reddit thread. Many of the watch hands appear to be stalled, and the crossover from each to the next– as when Mark Scout switches his wrist watch in preparation for his elevator descent into the workday of innie Mark S– doesn't match with our experience of the actors on screen. One of the few things we do know about the severance procedure is that it 'alters perceptual chronologies', and that this messing with a subject's sense of time is thought to 1) make them more adequate or productive in a certain kind of work (for why else would Lumon go to the necessary lengths to sever some employees) and 2) supposes to section off innie memories and experience from outie memories and experience. So the subject's subjectivity is marked by its sense of time, and Lumon's success (profitability?) hinges in some way on altering their employees' stable sense of it while in the space of the severed floor.

Mark S's temporal predicament here has been explained by a man whose last name we get by speeding up the saying of his own, Karl Marx (Mar-k-S). Logically speaking, Marx argues, there is an amount of time that goes missing in the worker's employment by way of a wage, when he advances some portion of his time to the capitalist in exchange for a pay-check one or more weeks later. I refer the reader interested in the details to chapter 20 of Capital Vol. I: but the essential point here is that it is through an obfuscation of the real value of a worker's time that the capitalist manages to produce surplus-value. The production of this kind of time-distorted surplus-value is the engine of capitalism as a social relation that appears, on the surface, to be equally fair to capitalist and worker alike. So the project of controlling 'perceptual chronologies' with which Lumon seems to be so concerned is perhaps not as esoteric and inessential as it might at first seem. Perhaps it is an embodiment of the core ingredient of the company's success as a company, of its incorporation as an entity that ought to be sustained even at the expense of its members' happiness, their health, and their livelihoods.